Come and See: Community-Led Evidence of Impact

When localization is discussed in operational spaces, the same concerns and questions surface repeatedly as constraints that shape decisions and implementation:

- “Can data generated outside formal systems be considered credible?”

- “How do we balance donor accountability requirements with community ownership?”

- “What happens to standards, safeguards and learning when control is reduced? Will standards drop? Will priorities drift? Will impact stall?”

These questions are not unfounded. They reflect real responsibilities related to accountability, stewardship of resources, fiduciary risk, evidence quality, program effectiveness and learning. But in many places, localization is already happening quietly, deliberately and with rigor. Not because a donor required it and not because an organization designed it that way but because communities themselves are choosing to lead, measure and act on the change they want to see.

So instead of answering these questions with frameworks or promises, this blog does something simpler.

It says: come and see.

Come and see what communities have already done, not with perfect conditions, not with unlimited funding, but with space, evidence and collective responsibility. The following cases, observed through Salanga’s CoLMEAL work, offer grounded responses, reflecting communities working within constraints, using evidence they generated themselves to drive change.

Let’s walk through these stories.

Question 1: Are communities ready to act?

Answer: Come and see Labongoguru, Northern Uganda.

Through a community-led census, residents of Labongoguru, a CoLMEAL- adopting community in Northern Uganda discovered that only 41.5% of their children were attending school. The reason was frequent flooding at a stream which made it unsafe for children to cross. What followed did not involve waiting for a project budget or appealing to an external actor. Instead, the Labongoguru community members engaged three neighboring villages (Lagaa, Ladiko and Lagaa West) and collectively decided to build a wooden bridge. The timber, labor and logistics were mobilized locally. No grant was attached to the decision.

Within a year, school enrollment rose to 94%.

The bridge did more than address education. It connected families to health facilities and local markets, producing unanticipated ripple effects. Readiness, in this case, was not something to be assessed. It was something revealed once communities were trusted to interpret their own data and act on it.

Question 2: Without tight control, won’t accountability weaken?

Answer: Come and see Murunga’ubuin, Kenya.

In Murunga’ubuin, the evidence of impact lives in charts created by the community themselves as records of a decision that reshaped their social fabric. Through CoLMEAL, elders, adolescents and families collectively decided to end the practice of child marriage.

What makes this significant is not only the outcome, but the absence of an externally imposed agenda. CoLMEAL did not dictate the goal. It simply created the space for collective reflection, discussion, action and learning. A space the community had not previously had. One year into the process, an assistant village chief shared with Salanga’s Senior CoLMEAL Advisor:

“CoLMEAL turned us into a community that works together for the change we want. It taught us to be accountable for our decisions and actions.”

Accountability, as seen here, is social, relational and ongoing. Neighbors holding one another responsible for shared decisions. Rather than standards slipping, Murunga’ubuin shows that when communities lead, they often hold themselves to higher standards than any external framework could enforce.

Question 3: Can community-generated data really unlock resources?

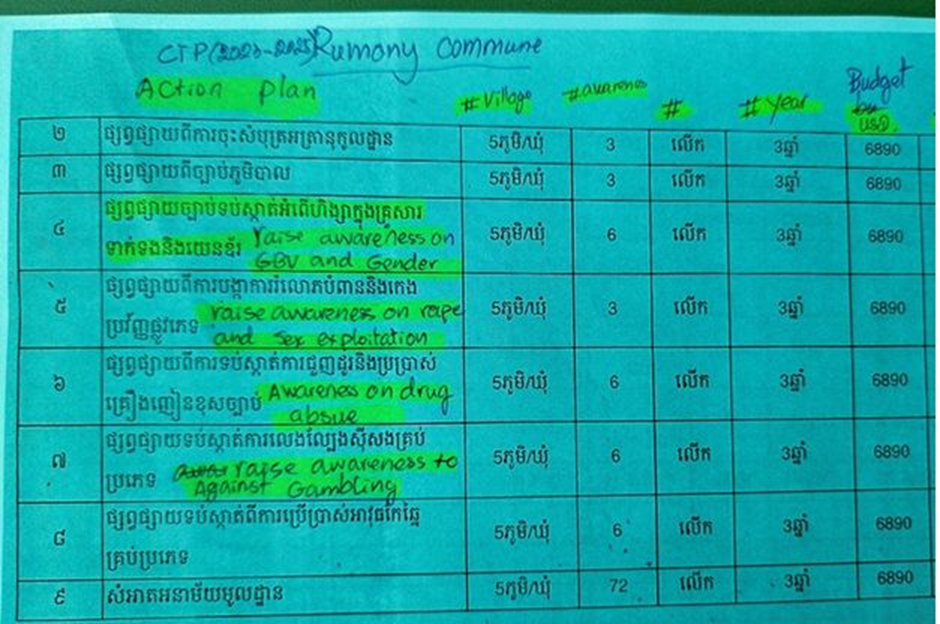

Answer: Come and see Rumony, Cambodia

One of the strongest arguments for maintaining control is the need for assurance. Donors need evidence. Governments need documentation. Trust alone is rarely enough and in Rumony, Cambodia, the community did not ask to be trusted. They presented evidence.

Through their CoLMEAL journey, the community generated and documented their priorities including addressing drug use, gambling, rape and gender-based violence across five villages. These were not kept as informal discussions. They were formally integrated into the Commune Investment Plan.

The result was undoubtedly something: three years of government funding secured to address community-defined priorities. This was not an intermediary-led advocacy. It was community-led negotiation, backed by data they owned and proving that when communities are equipped to produce good-enough evidence, they do more than plan. They gain access to systems and resources without needing others to speak on their behalf.

At Salanga, we work closely with communities using CoLMEAL, an approach that re-centers who defines problems, who owns evidence and who is accountable for decisions.

The stories above, shared by Salanga’s Senior CoLMEAL Advisor Alex Nayve, are grounded examples of what localization looks like in practice and with evidence. Together, they point to a reality the sector is still learning to trust: when communities lead with evidence, impact follows often faster and more sustainably than externally driven interventions.

Localization in practice demands two sides of the coin. Donors need credible data and trust. Communities need ownership. The task before us is not to choose between them, but to design approaches that hold both with integrity.

These stories do not argue that communities are perfect or that localization is simple. They show something more important:

- Readiness often appears after trust is extended, not before.

- Accountability does not disappear without control it changes form.

- Community-generated evidence can meet institutional standards while serving community agendas.

So perhaps the more useful question is not “Are communities ready?”

But rather: Are our systems ready to make room for what communities are already doing?

Localization in practice is not about letting go of rigor. It is about moving closer to the people who live with the consequences of decisions every day.

These communities are not waiting. They are already leading and the invitation is simple: come and see.

The projects referenced in this post were implemented in partnership with ADRA Canada and Global Affairs Canada:

Read more articles:

- Come and See: Community-Led Evidence of Impact

- How to Capture Fast, High Quality Lessons Learned in Remote Teams: Practical Tips Any Organization Can Use

- From Reporting to Learning: Making the Case for Mutual Accountability

- Collecting Useable Data: Turning Measurement into Learning

- Community-Led Development: The Heart of Localization